Is Inequality Inevitable?

Is Inequality Inevitable?

Wealth naturally trickles up in free-market economies, model suggests

Although the origins of inequality are hotly debated, an approach developed by physicists and mathematicians, including my group at Tufts University, suggests they have long been hiding in plain sight—in a well-known quirk of arithmetic. This method uses models of wealth distribution collectively known as agent-based, which begin with an individual transaction between two “agents” or actors, each trying to optimize his or her own financial outcome. In the modern world, nothing could seem more fair or natural than two people deciding to exchange goods, agreeing on a price and shaking hands. Indeed, the seeming stability of an economic system arising from this balance of supply and demand among individual actors is regarded as a pinnacle of Enlightenment thinking—to the extent that many people have come to conflate the free market with the notion of freedom itself. Our deceptively simple mathematical models, which are based on voluntary transactions, suggest, however, that it is time for a serious reexamination of this idea.

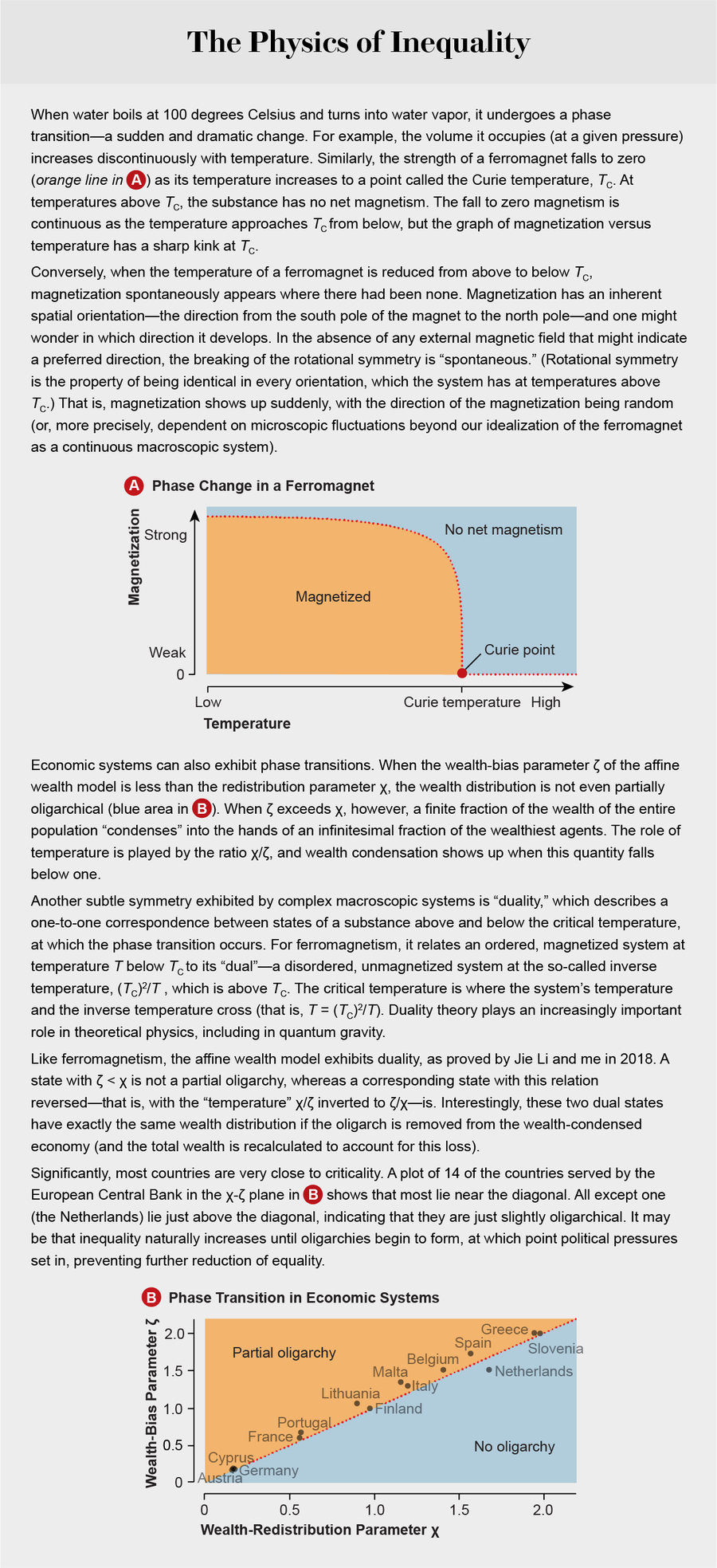

In particular, the affine wealth model (called thus because of its mathematical properties) can describe wealth distribution among households in diverse developed countries with exquisite precision while revealing a subtle asymmetry that tends to concentrate wealth. We believe that this purely analytical approach, which resembles an x-ray in that it is used not so much to represent the messiness of the real world as to strip it away and reveal the underlying skeleton, provides deep insight into the forces acting to increase poverty and inequality today.

Oligarchy

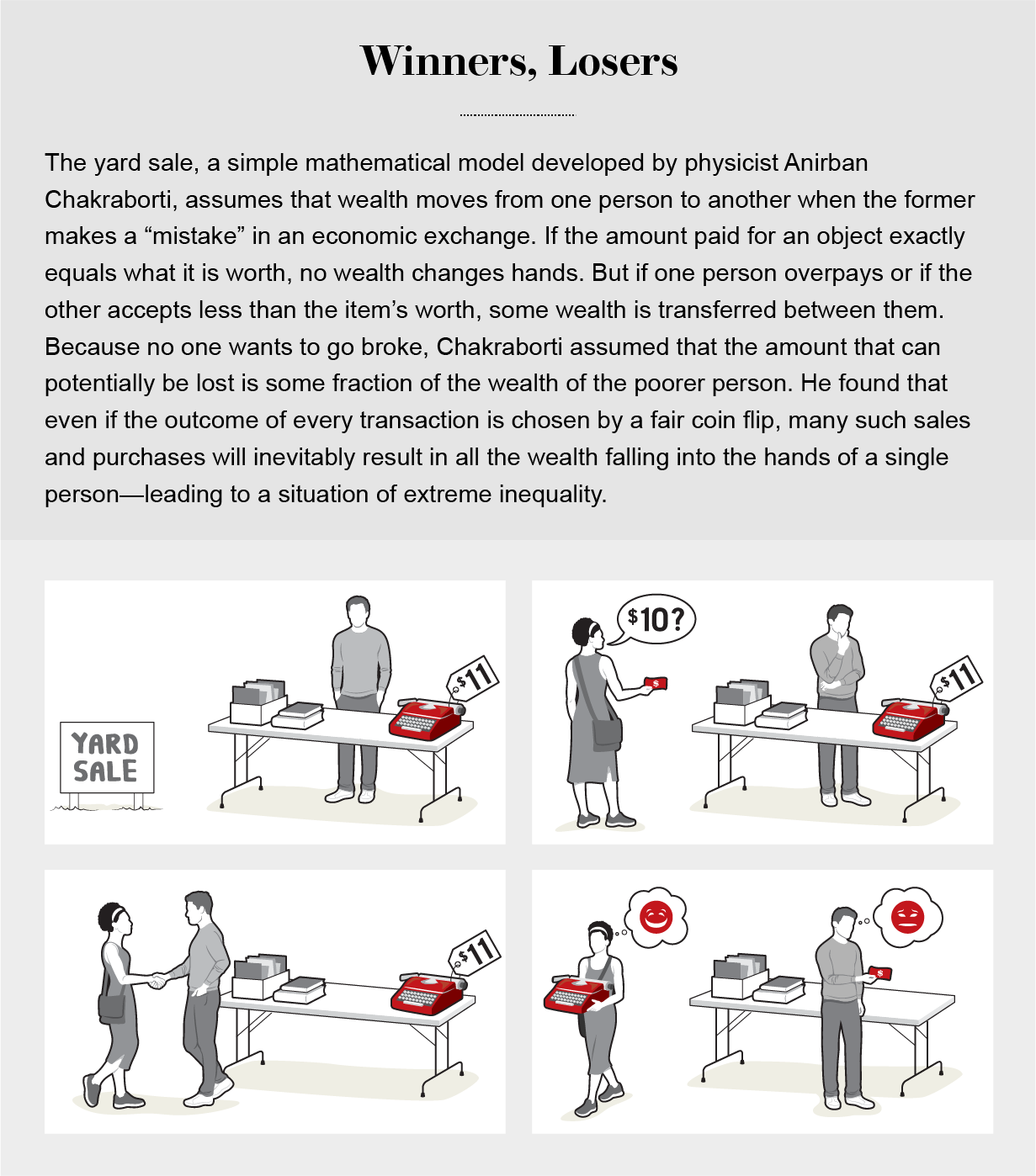

In 1986 social scientist John Angle first described the movement and distribution of wealth as arising from pairwise transactions among a collection of “economic agents,” which could be individuals, households, companies, funds or other entities. By the turn of the century physicists Slava Ispolatov, Pavel L. Krapivsky and Sidney Redner, then all working together at Boston University, as well as Adrian Drăgulescu, now at Constellation Energy Group, and Victor Yakovenko of the University of Maryland, had demonstrated that these agent-based models could be analyzed with the tools of statistical physics, leading to rapid advances in our understanding of their behavior. As it turns out, many such models find wealth moving inexorably from one agent to another—even if they are based on fair exchanges between equal actors. In 2002 Anirban Chakraborti, then at the Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics in Kolkata, India, introduced what came to be known as the yard sale model, called thus because it has certain features of real one-on-one economic transactions. He also used numerical simulations to demonstrate that it inexorably concentrated wealth, resulting in oligarchy.

...

We find it noteworthy that the best-fitting model for empirical wealth distribution discovered so far is one that would be completely unstable without redistribution rather than one based on a supposed equilibrium of market forces. In fact, these mathematical models demonstrate that far from wealth trickling down to the poor, the natural inclination of wealth is to flow upward, so that the “natural” wealth distribution in a free-market economy is one of complete oligarchy. It is only redistribution that sets limits on inequality.

The mathematical models also call attention to the enormous extent to which wealth distribution is caused by symmetry breaking, chance and early advantage (from, for example, inheritance). And the presence of symmetry breaking puts paid to arguments for the justness of wealth inequality that appeal to “voluntariness”—the notion that individuals bear all responsibility for their economic outcomes simply because they enter into transactions voluntarily—or to the idea that wealth accumulation must be the result of cleverness and industriousness. It is true that an individual's location on the wealth spectrum correlates to some extent with such attributes, but the overall shape of that spectrum can be explained to better than 0.33 percent by a statistical model that completely ignores them. Luck plays a much more important role than it is usually accorded, so that the virtue commonly attributed to wealth in modern society—and, likewise, the stigma attributed to poverty—is completely unjustified.

Moreover, only a carefully designed mechanism for redistribution can compensate for the natural tendency of wealth to flow from the poor to the rich in a market economy. Redistribution is often confused with taxes, but the two concepts ought to be kept quite separate. Taxes flow from people to their governments to finance those governments' activities. Redistribution, in contrast, may be implemented by governments, but it is best thought of as a flow of wealth from people to people to compensate for the unfairness inherent in market economics. In a flat redistribution scheme, all those possessing wealth below the mean would receive net funds, whereas those above the mean would pay. And precisely because current levels of inequality are so extreme, far more people would receive than would pay.